Pandemic Risk

Americans Mostly Safe From Ebola, Despite Rapid Spread

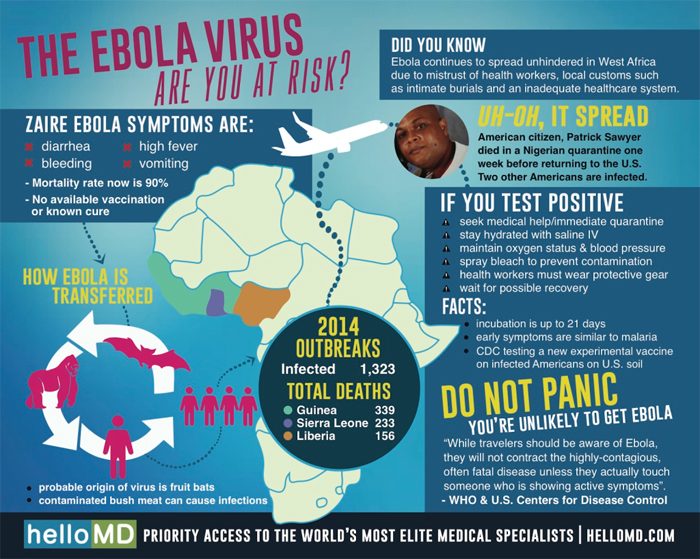

Since it was first discovered in early March, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa has reportedly taken up to 900 lives and infected about 1,700 others — a number that is likely to grow rapidly as affected countries (Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria and Sierra Leone) struggle to contain the disease.

The disease is increasingly emigrating to other countries, with at least two suspected victims in U.S. hospitals and a suspected Ebola death in the Middle East. Several Middle Eastern countries are reporting suspected infections.

A meeting on August 1 between World Health Organization (WHO) director Dr. Margaret Chan and leaders of Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia established a $100 million plan to deploy more medical professionals to the region.

In a transcript of meeting remarks, Chan said, “This outbreak is moving faster than our efforts to control it. If the situation continues to deteriorate, the consequences can be catastrophic in terms of lost lives but also severe socioeconomic disruption and a high risk of spread to other countries.”

Despite these bad omens, though, American business travelers and employees stationed in the region should be at low risk for infection as long as they take basic precautions.

“So long as they avoid heavily populated areas, practice standard universal hygiene precautions like hand washing, and stay out of hospitals and clinics where Ebola patients are treated, their risk should be lower,” said Dr. Robert Quigley, regional medical director and president of medical assistance, Americas region, for International SOS.

Armed gangs are chasing caregivers away from villages, while the infected hide, for fear that aid workers will cart them off to die.

Katherine Harmon, health intelligence director at iJET International, said her company advised that the affected countries and surrounding areas were safe for travel. “If you’re not a health care worker, you have low risk of being exposed. Stay away from large crowds; avoid people who are sick in general; practice good personal hygiene. The risk of contracting Ebola is quite small.”

The rapid spread of disease among these impoverished countries, she said, is mostly due to cultural practices. In burial practices, for example, the bodies are washed, and the deceased’s loved ones customarily touch the body as a sign of reverence.

“They don’t understand that those bodies are still infected, and everyone who touches them is at risk,” she said. “And if somebody tries to come in and take the bodies away to cremate them, they take it as a religious slap in the face.”

Health ministries in the affected countries also separate physician licensing into Western medicine practitioners and homeopathic practitioners. “There’s a very strong community sentiment that does not believe in Western medicine. They believe doctors want to preform experiments on them,” Harmon said. “The biggest risk is from patients who have absconded or are hiding their symptoms, refusing to seek treatment.”

“If you’re not a health care worker, you have low risk of being exposed. Stay away from large crowds; avoid people who are sick in general; practice good personal hygiene. The risk of contracting Ebola is quite small.” — Katherine Harmon, health intelligence director, iJET International

Ebola’s mortality rate is around 90 percent, but early treatment can improve chances of survival by about 30 percent. Police in some countries have started to conduct house-by-house searches to locate infected people.

Harmon also advised U.S. workers or visitors in the region to carry their own medical kits, as supplies and availability of doctors will run low. Self-care may be necessary, she said, since not all third-party medical assistance providers will be able to evacuate employees due to international regulations and individual protocols.

“You may be stuck there,” she said.

The affected countries have ramped up efforts to quarantine the disease over the past few days. Sierra Leone declared a state of emergency, Liberia has sealed its borders, and two major Nigerian airlines will no longer fly into countries where Ebola has been confirmed. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has recommended deferring all non-essential travel to the region. WHO, however, has not issued any travel or trade restrictions.

Airports servicing flights in an out of the regions are screening passengers for symptoms, which will help contain the disease, Harmon said. “The best approach is for people to understand what’s going on and be cooperative with these measures.”

Though the Peace Corps and other aid groups have pulled out volunteers, “lots of organizations, such as NGOs, are heading in there anyway,” Quigley said.

“All companies have different thresholds for evacuation and different levels of risk tolerance. They should be looking through their travel tracker processes to identify anyone who is there and potentially at risk. They are having to work with local authorities, who have some control over how and when people can exit.”

“Companies should evaluate their risk tolerance, talk to their insurance people and assistance providers and make sure they’re covered,” Harmon said. “Know what your plan is to get out if something happens.”

Quigley added, “You need to go back to your business continuity plan, which traditionally would include an infectious disease plan and pandemic plan. If you don’t have one, this kind of event should motivate companies to develop one. You can bet there is some exposure there for companies in every industry segment.”

In addition to supplying more nurses and physicians, WHO’s new plan also aims “to increase preparedness systems in neighboring nations and strengthen global capacities.” This should slow the transmission of the Ebola virus within the most affected countries and prevent its spread across borders.

The plan also includes improved communication efforts, advising how to avoid the infection, how to recognize its symptoms, and how to report suspected cases. “Referring people infected with the disease for medical care, as well as psychosocial support, are key,” the statement said.

“It can take 21 days to prove you are Ebola-free if you’ve been quarantined,” Harmon said, “Once these countries have a zero-case level of Ebola patients, it will take up to 42 days for them to be declared Ebola-free. It’s going to be a while before things are back to normal.”