Enforcing Safety

Retaliation is Futile

Between 2011 and 2013, 13 workers at The Ohio Bell Co., known as AT&T, reported being injured on the job. The company subsequently suspended those workers for up to three days without pay for violating workplace safety rules, which — presumably — was the cause of their injuries.

The company claimed it punished the employees for flaunting safety standards, but that’s not how the U.S. Department of Labor saw it. An investigation by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) found that the suspensions were not legitimate and were in fact acts of retaliation against the workers for reporting their injuries.

The Department of Labor filed suit alleging “the company violated the whistleblower provisions of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970.” Those provisions state “No person shall discharge or in any manner discriminate against any employee because such employee has filed any complaint.” OSHA enforces 22 similar statutes under its “Whistleblower Protection Program,” and has recently become more aggressive in going after employers that raise even the smallest of red flags.

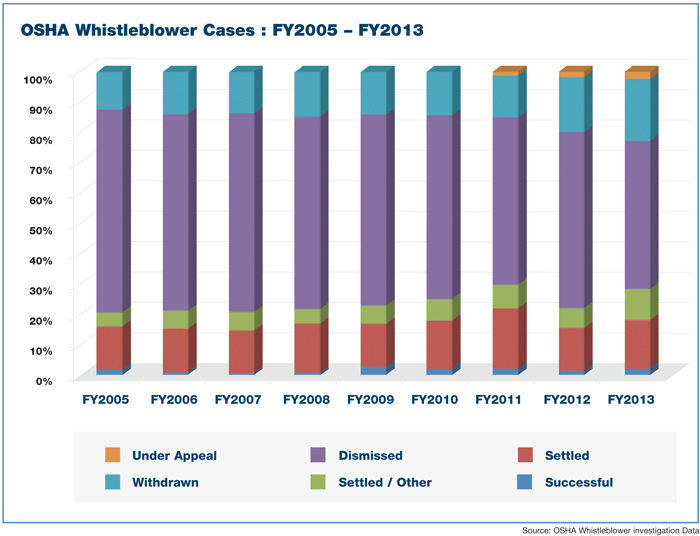

The whistleblower case against AT&T is just one of 2,957 that the Department of Labor received in 2013, up from 1,934 in 2005. The jump was spurred by a reprimand from the Government Accountability Office in 2010. An audit found that “OSHA has done little to ensure that investigators have the necessary training and equipment to do their jobs, and that it lacks sufficient internal controls to ensure that the whistleblower program operates as intended.”

Since that slap on the wrist, OSHA has upped its emphasis on anti-retaliation investigation and litigation, hiring 25 new investigators and 75 support staff personnel in 2011, and requesting funding for 45 more investigators in 2012. Separate from compliance officers, these investigators are dedicated solely to whistleblower cases.

OSHA isn’t only looking into employers’ disciplinary actions; they’re scrutinizing safety incentive programs as well. Any program that rewards employees for low injury rates could be seen as a form of intimidation, encouraging workers not to report injuries for the sake of receiving a good performance review, a cash bonus or some other prize.

So how does a well-intentioned employer get its employees to adhere to safety standards without invoking an OSHA suit? And in the face of a retaliation allegation, how can it prove that its actions were fair?

Litigation on the Rise

“Theoretically, an employer can discipline an employee for being unsafe on the job, but the defense becomes technical,” said Robert Tice, an attorney with law firm Collins Einhorn Farrell. “The employer has to show that they discipline people the same way all the time whether or not they’re injured. They better show comparable employees who’ve been disciplined when there was no injury or complaint.”

“As a kid playing basketball, we had a ‘no blood, no foul’ rule,” said Bill Spiers, risk control services manager at Lockton. “Basically if there was no injury, it wasn’t a foul.” That’s exactly the mentality that can get employers in trouble. Punishing employees only when an injury is reported shows an employer to be discriminatory. Consistency is key when it comes to safety enforcement.

Employers will bear the burden of proving that the employee knew of the safety rules and discipline policy before the injury took place. That means having the policy in writing, preferably signed by the employee at the time of his or her hire, and having clear warnings posted around the workplace stating what the safety protocols are as well as consequences for breaking those protocols.

Without those, “the employer will almost always be found at fault for having an unsafe workplace” if an injury is involved, Tice said.

While most whistleblower cases OSHA sees are found to be without merit, employers should expect investigators to become more suspicious. An alert published by the labor and employment practice group of law firm Morgan Lewis in 2012 advised employers to “be prepared for longer and more invasive investigations that will include more document requests and witness interviews. An increase in meritorious findings is one of the main objectives behind revamping OSHA’s Whistleblower Protection Program.”

Employers should also review their safety rules for clarity and specificity. A 2012 memorandum issued by OSHA Deputy Assistant Secretary Richard Fairfax — called simply the Fairfax Memo — stated that “The nature of the rule cited by the employer should also be considered. Vague rules, such as a requirement that employees ‘maintain situational awareness’ or ‘work carefully’ may be manipulated and used as a pretext for unlawful discrimination.”

Jury bias adds to the challenges for employers accused of retaliation.

“Jurors seem to understand retaliation cases more than discrimination cases,” Tice said. That means that even if an employee’s initial complaint against their employer is without merit, they could still win a retaliation case if they can show they were treated worse in any way after the complaint was filed. For employers, that’s a “no-win situation.”

Nontraditional Safety Programs

The best way to avoid this conundrum, OSHA says, is to prevent initial complaints in the first place by implementing nontraditional safety programs.

Nontraditional or behavior-based programs focus less on reducing injuries and more on getting employees involved with other safety activities, like joining safety committees, participating in an internal accident investigation, self-auditing and mentoring new hires. OSHA has voiced its support for these types of programs that don’t discourage reporting of injuries.

“Traditional safety incentive programs use lagging indicators, like injury rates. OSHA leadership has spoken out against this and any measure that ties into the way they report or record injuries,” said Jon Snare, a partner in the labor and employment practice group at Morgan Lewis. “When it comes to best practices, employers may want to consider nontraditional safety incentive programs.”

“Involvement equals commitment. Ninety percent of workers will do the right thing, and positive recognition helps encourage that.” — Bill Spiers, risk control services manager, Lockton

The Fairfax Memo criticized traditional safety programs that “unintentionally or intentionally provide employees an incentive to not report injuries.” Nontraditional programs, it said, can still incentivize employees with rewards like “throwing a recognition party at the successful completion of company-wide safety and health training.”

Employee surveys can help measure the effectiveness of these programs, Lockton’s Spiers said, though he expects them to perform better than a discipline policy.

“Involvement equals commitment,” he said. “Ninety percent of workers will do the right thing, and positive recognition helps encourage that.”

Discipline with Caution

That being said, OSHA still recognizes an employer’s right to use discipline. The Fairfax Memo acknowledged that discipline can be a legitimate part of a company’s safety policy, as long as it is enforced consistently and documented diligently. Because workplace risks vary widely from company to company, OSHA issues no hard and fast guidelines for how employers should implement and enforce safety rules.

“Communication has to be the No. 1 thing,” said Michael Stack, principal at Amaxx Risk Solutions. “If you’re communicating your safety policy to employees consistently and always following it, whether someone was injured or not, then you avoid the variation that can lead someone to claim the action is discriminatory.”

“If you told me from the beginning that I’d lose a day’s pay if I remove a safety guard, I’m more likely to follow the rule.” — Michael Stack, principal, Amaxx Risk Solutions

Stack also advocated taking a strict approach with discipline, if it will be used at all, to avoid misinterpretation or variation in its enforcement. Verbal warnings, for example, are typically the first stage of discipline, but accomplish virtually nothing as far as preventing an accident or injury.

“People don’t put value in [verbal warnings],” Stack said. People are apt to blow off a verbal reprimand and continue unsafe practices until they experience more serious repercussions. “If you told me from the beginning that I’d lose a day’s pay if I remove a safety guard, I’m more likely to follow the rule.”

Discipline can be more effective if verbal and even written warnings are skipped. Handing out serious punishments right away, like docking pay or suspending employees, quickly drives home the importance of safety. Employers should be protected in using such punishment if they continually make clear to employees that those consequences exist.

Safety Culture

Even the most consistent discipline policy, though, cannot achieve the same results as a strong culture of safety, according to Stack of Amaxx.

“There’s no incentive that’s as important as the culture of safety, and that comes from the top,” Stack said. “Nobody wants to get hurt; the problem comes in when other things become more important, like emphasis on productivity or efficiency before safety. I won’t take off a safety guard if I think I’ll get hurt, but I might do it if I’m afraid of losing my job because I’m not performing efficiently enough.”

Safety policies should be viewed on the same level as HR and other work policies, Spiers said. For example, a work site manager once told Spiers that he could not “make” his forklift drivers wear their seatbelts.

“Why?” Spiers asked him. “Wearing the seat belt should be seen the same way as showing up to work on time. If your shift starts at 7 a.m., you’re there at 7 a.m. If you’re supposed to wear the seatbelt, you wear the seatbelt.”

It’s unclear exactly how the workers at AT&T incurred their injuries, when they reported them, when they were disciplined, how that discipline was delivered, and whether or not they knew of the safety rules and discipline policy in place.

But regardless of whether or not the case is found to have merit, the suit reminds employers that retaliation claims are an increasingly prominent risk. To keep them at bay, upping the emphasis on safety — not solely injury prevention — really should come first.