Climate Change

Rising Threats in the Public Sector

In Orange, Texas, a March public meeting to review storm surge suppression options for the Gulf Coast Community Protection and Recovery District had to be rescheduled to April 14 because of — wait for it — widespread flooding.

Irony aside, nearly 140 miles of the Sabine River flooded for four days, closing down almost all major roads that crossed this watery Texas-Louisiana border.

The flood and delayed meeting are a clear example about the very real impact climate change is having on low-lying areas all around the U.S. coasts. The Texas Governor’s Commission for Disaster Recovery and Renewal program estimates that it may cost as much as $11 billion to protect that area of the Gulf Coast.

“Nobody is sticking their head in the ground as far as I can see.” — William F. Becker, national public sector practice leader, Aon Risk Solutions

That’s a good investment, however, since Hurricane Ike in 2008 wrought $29 billion in property damage, making it the most expensive storm in the state’s history and the third costliest in the country, according to the Texas Engineering Extension Service report.

Texas officials are not alone in facing such challenges.

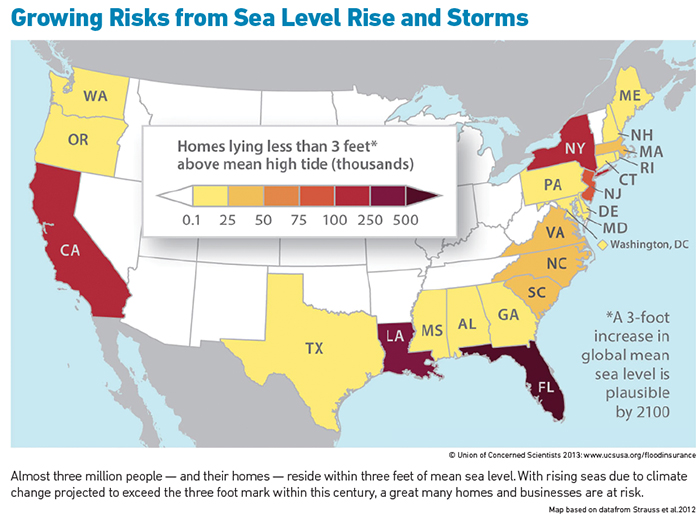

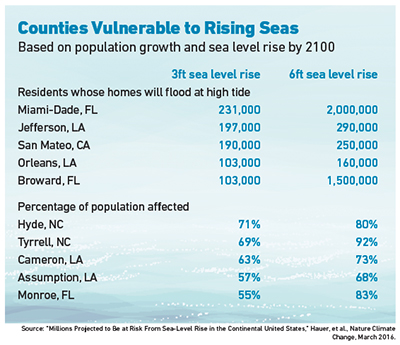

Coastal communities such as New York City, Norfolk, Va., Miami-Dade County, and Seattle lie at or below sea level, making them vulnerable to storm surges and flooding, especially in the face of the rising sea levels and increased storm activity predicted for the coming decades.

The key question for the public sector is how to affordably protect both residential and business properties as well as public infrastructure such as roads, bridges, utilities, water treatment plants, and other assets.

For many communities, the answer is to do more accurate risk modeling; do short- and long-term planning; build traditional “gray” defenses such as dams, levees, walls, and sea gates as well as natural “green” defenses to reduce storm surge impact; and work with insurers and reinsurers to rebound from losses made inevitable by climate change.

“Nobody is sticking their head in the ground as far as I can see,” said William F. Becker, Aon Risk Solutions’ national public sector practice leader. Instead, communities are balancing what can be done over the next few decades with current engineering and technology, while keeping an eye out for what may be possible with new technology by the year 2100.

Starting Small

However, budgetary pressures make many large-scale projects unaffordable, so public entities are maintaining the current infrastructure as best they can for now, said Becker, whose company also helps to administer the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP).

Some cities have begun implementing protective strategies with a lower price tag, such as prohibiting land clearing near flood-prone areas, planning for public green spaces to absorb water, elevating streets over time, providing dunes on the coast, and heightening sea walls, among other solutions.

Some cities have begun implementing protective strategies with a lower price tag, such as prohibiting land clearing near flood-prone areas, planning for public green spaces to absorb water, elevating streets over time, providing dunes on the coast, and heightening sea walls, among other solutions.

Tackling the problem with small, affordable strategies will give public sector organizations more time “until new and highly technical strategies can save these critical vital communities going forward,” Becker said.

Others are looking to partnerships to broaden their access to solutions.

One example is Miami-Dade County, which launched an innovative program in partnership with The Nature Conservancy (TNC), catastrophe modeler Risk Management Solutions (RMS), engineering company CH2M, and the American Red Cross/Red Crescent’s Global Disaster Preparedness Center.

The collaborators will work on various aspects of two demonstration projects that will measure the effects of green defenses such as salt marshes and mangrove forests in protecting the region from the severe storms that arise in the Atlantic’s Hurricane Alley.

Robert Muir-Wood, chief research officer, RMS

This is the latest research project that RMS undertook to help model the protective impact of biological defenses. Working with communities on both coasts — including Norfolk, Va., and the Seattle region’s Puget Sound — “RMS has begun showing how we can quantify the reduction in risk using our storm surge modeling capability for coastal risks,” said the modeler’s Chief Research Officer Robert Muir-Wood.

“Our [modeling looks at] the full sweep of potential hurricanes and the storm surges they generate, and takes it all the way through to the damage and the quantified loss to property, which may be inland of the coastal areas,” Muir-Wood explained.

“We can actually quantify the benefits of one form of coastal defense [marshes]. That opens up a much bigger conversation to not only other classes of biological defenses but also to think through how can you combine a mixture of biological and gray defenses to provide really good protection.”

This kind of assessment is critical for communities to understand the complete impact of storms on local government budgets, noted Kathy Baughman McLeod, managing director of TNC’s coastal risk and investment.

“We have found that local governments and governments in general don’t know what their risk is,” said McLeod. “And then, when they make [storm-related] repairs, they pay for it out of all different buckets [such as public works, parks and recreation, etc.].

“When we ask, ‘What are you spending each year?’ they don’t know. They have the awareness but the [quantitative analysis] is not there.”

Impact on Rates

TNC’s project will help develop trusted metrics about both green and gray defenses that can eventually be adopted to set more accurate NFIP prices and quantify total risk. In addition, on April 1, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) implemented more rigorous guidelines for accurately assessing flood risk to help set more appropriate insurance rates.

While property owners and local governments in some communities will pay higher rates that are more commensurate with the actual risk, communities that adopt better defense strategies will see their rates decrease.

While climate change may have the greatest impact on coastal communities, the interior of the U.S. will face changing weather patterns as well.

For example, New Orleans got good news from FEMA in April, nearly 11 years after Hurricane Katrina devastated the city. With about $14.6 billion in improvements made by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the below-sea-level area now has a new defensive ring of protective levees, floodwalls, and floodgates.

Work is continuing on renovations to the city’s drainage system as well. For many residents and businesses, the new maps mean lower insurance rates.

Muir-Wood said expect to see more municipalities and other public organizations create the position of chief resilience officer, just as Miami-Dade County, Norfolk, San Francisco, New Orleans and other cities have done with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation as part of its 100 Resilient Cities project.

This new office will coordinate work across departments and jurisdictions as well as with outside organizations to plan for and respond to weather-related events as well as other threats, such as fire, tornadoes or civil unrest.

Another trend, he said, is that catastrophe modeling tools previously used solely for insurance risk assessment will become more commonplace for big cities, letting them conduct a cost-benefit analysis for various alternative actions to reduce that risk.

Joe Caufield, chief underwriting officer, government risk, OneBeacon

Finally, understanding weather-related exposures is still going to be critical for public sector entities, said Joe Caufield, chief underwriting officer for OneBeacon’s government risk operation.

“Some information is presented in a highly dramatic fashion,” he said. “The feedback we hear is that risk managers and city managers are overwhelmed by [threats] and don’t see them as actionable … but we don’t encounter too many climate change deniers.”

Instead, public sector organizations are studying their exposure for critical assets such as wastewater management facilities and 911 communications centers. They’re making plans for protection and upgrading, especially if the facilities are right on the edge of FEMA flood map outlines that may not have been updated in 40 years.

One thing to remember about climate change, Caufield noted, is that while it may have the greatest impact on coastal communities, they are not the only areas that will have to contend with climate threats.

The interior of the U.S. will face changing weather patterns as well, especially with greater temperature variations between severe cold and increased heat. That equals a more severe spring tornado season. &